The five essays in this publication are bound together, look at them as sections in a research project. They cross-reference each other and generally reinforce each other. The guide is meant to help readers understand the main concepts and motivations commonly used throughout all the essays.

When you read through the publication remember that it is a research work in progress and it very much depends on and seeks comments from its readers. It will be a long time before it reaches a definitive form, if ever.

The terms AI, Democracy, and Human Values, are usually light and imprecise in public discourse. They are not for me, I tend to look at them as heavy, requiring constant sharpening of their meaning and also criticism coming from people who have had different experiences using these terms.

The term Democracy in particular has been abused and overused, with many of its aspects becoming targets of meaningless political debates. Individuals and parties routinely accuse opponents of undermining democracy, without specifying what that undermining consists of.

“I cannot too often repeat that Democracy is a word the real gist of which still sleeps, quite unawakened, notwithstanding the resonance and the many angry tempests out of which its syllables have come, from pen or tongue. It is a great word, whose history, I suppose, remains unwritten because that history has yet to be enacted.” - Walt WhitmanDemocracy versus Liberalism

Democracy and liberalism are often associated, but they don't always go hand in hand. Democracy is a system of government based on selecting government officials through universal suffrage, while (classical) liberalism is an ideology, based on the belief in individual liberty and equality, and support for individual rights and limited government. Liberal democracy is a political ideology (and a system of government) that combines representative democracy with classical liberalism. This combination, as a starting point before we make further refinements, is what we mean by democracy in this publication.

Liberal Democracy versus Nationalism

We will consider liberal democracy to be a national choice, i.e. a choice that nations of the world may or may not make. It is possible that an enlightened autocracy (as with Plato’s philosopher-king) could use AI to build a well-functioning society protective of human values. China and Russia have prospered economically under the leadership of Xi and Putin respectively, and many citizens of China and Russia view them as soft benevolent autocrats. Although clearly in the eyes of the Western liberal democracies, who place a premium on individual liberty, they are not.

Regardless, we would be better served in this publication if we kept that disagreement to ourselves and respected the choices that others make. So this publication refers only to those nations of the world that have chosen liberal democracy as their preferred solution and analyzes the interplay between AI, democracy, and human values within those nations.

The clip below sums up this approach well, just beware that the title of the clip is not right. The talk is about the end of liberal hegemony, not the end of liberal democracy. Equivalently, you may read that title as “imposing liberal democracy on the entire world is over”. At the same time, liberal democracy in the US and many other countries is alive and well and hopefully redefining itself in stronger ways in the age of AI. This redefinition is at the core of our publication.

After having set that limitation, it is worth noting when comparing systems of government that, although individual choices may vary greatly, people tend to vote for the better system by immigrating from one system to another, a very compelling way to vote. And liberal democracies do attract more immigration than any other system. Wait for Francis Fukuyama to make that point in the clip below.

In the age of AI, Democracy as a Mathematical Object

In this publication, we’ll often look at democracy as a mathematical object, more precisely a formal system, with its axioms and its rules of deduction. Sometimes the formality is spelled out, other times it’s not. Sometimes we formulate democracy in terms of game theory, with the objective of the game being the maximizing of collective well-being. The US is not the only inspiration for such a formal model and the US implementation may break down after 2024. We look at the US as an ongoing experiment in democracy, rather than a well-established one.

The US Constitution could also be imagined as such a mathematical theory, although not fully formalized, and then it is easy to see the Supreme Court justices acting as mathematicians tasked with checking whether certain situations or cases brought before them are theorems or not, by trying to prove or disprove them. It then appears with more clarity, by association with mathematics, that the Supreme Court deals with provability, not with truth. Conflating provability with truth is a source of many misgivings in the US democracy, but the distinction is very clear in mathematics.

In the age of AI, Democracy as a Foundation Model

Democracy depends on the participation of its citizens and is therefore related to the statistical processing of large amounts of data generated by its citizens. We will at some other times look at democracy as precisely such a statistical learning system, where continuous learning is obtained through citizen participation.

One thing we have to clarify here. When we mention a foundation model for democracy, we do not mean a foundation model built in the usual high-tech way. More specifically, we do not mean a model built by AI developers, we mean a continuously trained model done through citizen participation, developed and maintained by a governmental institution, and subject to rigorous vetting and frequent audits. Of course, such a model does not currently exist, and it is one of my fantasies to use this publication as a source of input for building one.

To stress that point a bit further, even along strictly technological lines, current foundation models, and especially the Large Language Models (LLMs), cannot be the basis of such a foundation model because they are not very good at interpreting complex social and philosophical concepts, as it can be seen in the clip below.

Moreover, building such a foundation model through a democratic process would be an ideal test bed for that old pronouncement that only properly educated citizens should participate in the democratic process. A foundation model can contain a parameter that would specify the level of education that a citizen must have for his/her input to be accepted. This education level of a citizen is determined from the data that the model itself has accumulated about the citizen, not by a formal education degree granted to the citizen by some school. The education level parameter can be dialed up or down and the consequence of setting a new level, namely effectiveness of governance, can be statistically measured.

AI Offers Us a Unique Opportunity to Get Democracy Right

Progress in democratic governance will likely be achieved by combining the deductive system above (democracy as a mathematical object) with the statistical learning system (democracy as a foundation model). Many other human endeavors are already seeing significant progress by combining two such systems. See the AlphaGeometry system for example, or the Wolfram Alpha/ GPT pairing. Simplistically, this combined system will look as the following:

There is a lot to unpack in the diagram, but we’ll leave that unpacking to a future essay dedicated to it. Suffice it to say that we will try to focus on the participation arrow until that essay is published. How would the other components work, briefly?

Suppose we have a statement about a certain situation in a democracy. We want to prove or disprove that statement (prove its negation) with the deductive system that governmental legislation has produced.

For most such statements, that would be difficult to do because there is not enough data coming from the public domain or from citizens’ participation to allow the foundation model to recognize patterns of provable statements. These statistical models are only so successful because of the massive datasets they are trained on.

Let’s look at how proofs are generated by humans in two cases that the reader has seen in high-school geometry and algebra. (We’ll then see how the deductive part of the democracy model can generate synthetic proofs to be used in training of the statistical learning part.)

The first example is this: prove that the sum of the angles in a triangle is 180 degrees. One has to draw an additional construction, namely a line through the top vertex that is parallel with the base line of the triangle. Then apply the parallel postulate of Euclidean geometry to the two side lines of the triangle, concluding that angle A at the top of the figure is the same as angle A of the triangle, and similar for B. So it follows by looking at the three angles circled in red that they all add up to 180 degrees. Now, notice the importance in the proof of adding that parallel line through the top vertex.

A second example of such auxiliary constructions comes from algebra. It’s the proof of the quadratic formula, i.e. the formula for the solutions to the equation:

a is assumed to be any real value, except 0. Here is the proof. Notice the auxiliary constructions of dividing by a, and completing a square on the left side (shown in red).

So, using the concept of auxiliary constructions shown by these two examples, in the initial training phase of the foundation model, the deductive system generates a lot of synthetic proofs of various other statements by adding such additional constructions, and feeds those proofs to the foundation model (via the feedback arrow), allowing it to learn patterns of democratic proofs. This synthetic data complements the other “proofs” that individual citizens supply through their participation.

When presented with a new statement, the foundation model will then try to augment it with additional constructions to create a proof that resembles a recognizable proof pattern. It predicts that it is a good proof and then it submits that proof (via the facts arrow) to the deduction engine for verification.

It’s a mouthful, but it will have to suffice for now.

“ It's coming to America first, ... the cradle of the best and of the worst. It's here they got the range ... and the machinery for change... And it's here they got the spiritual thirst.”

- Leonard Cohen, in the song below (We’ll propose that AI is that machinery for change.)

Why Does Morality Occupy Such a Central Role In this Publication?

The reader is probably aware that a publication such as this one is bound to run into philosophical issues all the time. Some issues are related to the future of humanity and the extent to which AI will impact that future, in general, and independent of a democratic system of government. These issues belong to the philosophy of artificial intelligence, and we touch on them only tangentially.

Then some issues belong to a philosophy of democratic governance, and those issues we touch more directly. But there is one part of philosophy that is most intimately connected to the publication because the publication is about the interaction between AI, democracy, and human values, not about those subjects in separation. It is morality. When we talk about democracy upholding human values, that implies morality. When we talk about aligning AI with human values, which is the main problem of AI, that alignment also implies morality.

In the diagram above, we called the input from the citizens of a democracy into our proposed democracy model, participation. And we called the input from the government, legislation. Both depend on issues of morality. Legislation in general, and AI regulatory legislation in particular, is covered in the People-Powered AI Governance essay. In this Reader’s Guide, we say a bit more about participation, since it will more directly concern the reader.

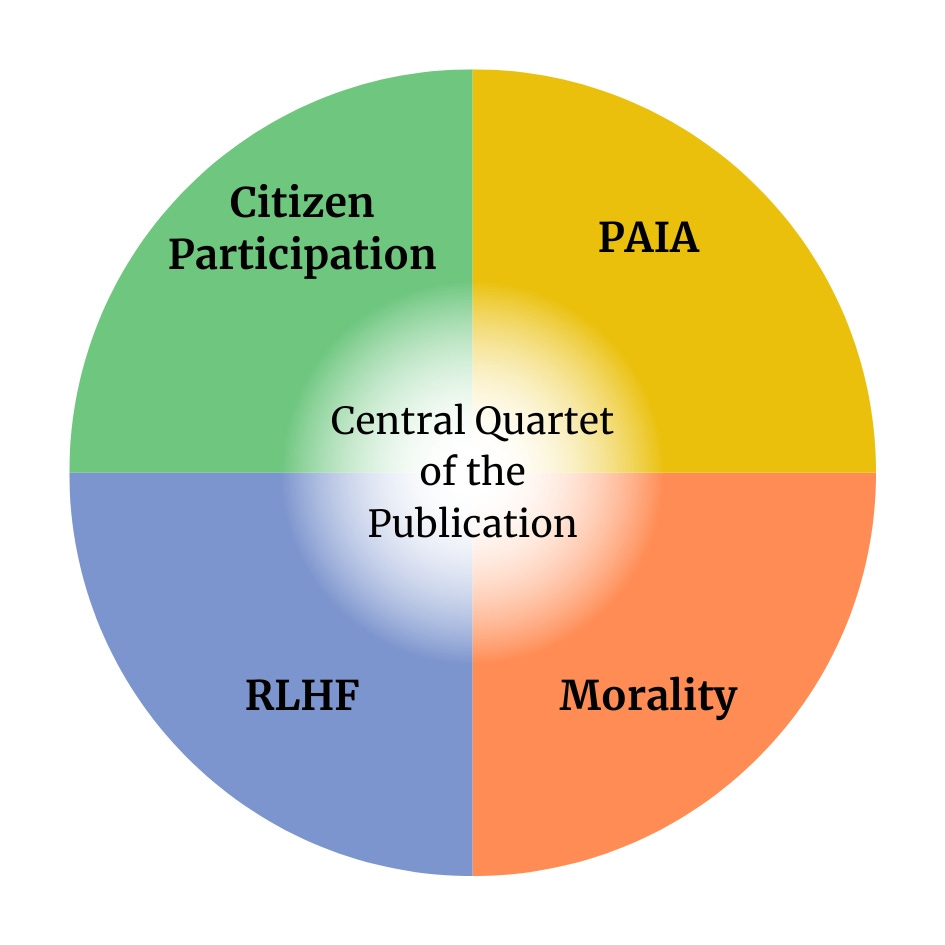

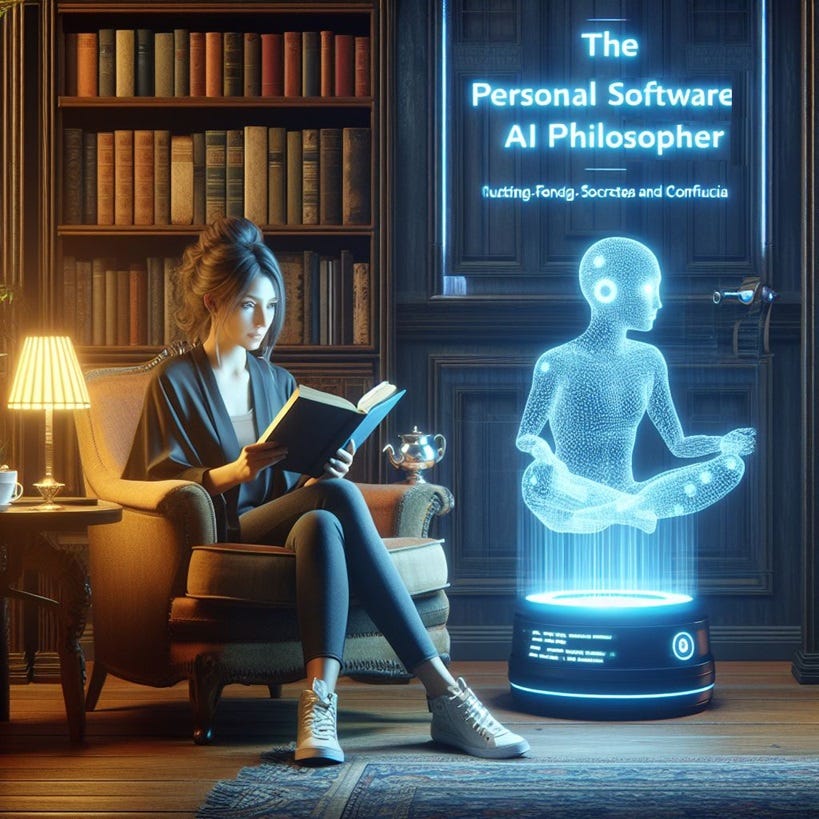

Participation can be looked at as a more general form of RLHF (Reinforcement Learning with Human Feedback), the central AI technique of this publication. The technique is described in detail in the AI Language Models as Golems essay; it’s how Large Language Models (LLMs) are aligned with human values. By extension of that method of training LLMs, the participate input from citizens into the foundation model that is part of the democracy model (shown above) is a form of RLHF; the citizens prompt the foundation model and score various outputs given by the foundation model to their prompts. In time all of this activity will be done by the citizen’s personal AI assistant (PAIA), the subject of the Personal AI Assistant post, a work in progress.

We can sum all this up in the following diagram, which we will refer to frequently:

For the more technically inclined reader, I present the issue of morality in the age of AI, and the need for a formal specification of morality, in the section Formally Specified Morality and Benevolent AI of the article Superintelligence and God, on my website: Artificial Intelligence, Dreams and Fears of a Blue Dot.

Criticisms of Democracy: What Can Go Wrong?

"Democracy and the one, ultimate, ethical ideal of humanity are to my mind synonymous." - John DeweyThe publication, as the reader may have noticed already, lines up with Dewey’s optimistic view, and tries to make the case that AI presents us with a unique opportunity to realize that view. But before making that case, we have to acknowledge that democracy has been a most difficult system to implement and maintain; many things can and do go wrong, and many philosophers have argued against it eloquently.

Many criticisms revolve around the notion that when everyone participates in decision-making without understanding what it is that they are deciding, chaos will follow, and therefore only the “educated” citizens should be allowed to participate. We will make the case that in the age of AI, citizens endowed with a personal AI assistant, should be able to reach an acceptable level of education and be able to participate without chaos.

Notable criticisms come from Plato, Socrates (which we will bring up later below), and Nietzsche.

Nietzsche's radical perspective on the merits of aristocracy is perhaps the most pointed criticism, contrasting it with perceived weaknesses of democracy and emphasizing the importance of aristocratic morality in supporting high culture and the development of the "Ubermensch". Nietzsche critiques democracy for its tendency to suppress greatness in individuals, supposedly favoring mediocrity and equality over excellence and heroism.

My view is that the modern liberal democracies (the US for example) have proven Nietzsche wrong, that greatness in individuals and heroism have not seen any retreat and that in fact, the opposite has happened, as extraordinary advancements in arts, humanities, science and technology, have been made by many such individuals, most of whom would not have cared to be labelled "Ubermensch".

The biggest and very real danger a democracy faces is demagoguery, and this is what we analyze next, as we have a very pointed example staring at us in 2024.

Test Case for Democracy: Facing Demagoguery

The 2024 presidential campaign of Donald Trump has been shaping up as an unprecedented challenge to the US democracy, which challenge should not come as a surprise since the former president has shared his agenda on multiple occasions.

More broadly, while Project 2025’s stated goal is to reshape the federal government with conservative principles, it effectively serves as a roadmap towards an autocracy rooted in Christian nationalist ideals, not what the Founding Fathers intended.

At the core of its mission, the project stipulates that "freedom is defined by God, not man", while this publication is based on the opposite stipulation that "freedom is defined by man, not by God". Very much a Kantian stipulation. The mistake that Project 2025 makes is to assume that Trump will support its ideology. He does not have an ideology, everything revolves around the Me goal.

To be fair, the extreme polarization in the US that makes us particularly vulnerable to demagoguery comes from all sides of the political spectrum. The push of identity politics from the left and the extraordinary confusion among progressives regarding the Israel-Hamas conflict are just two examples showing that reconciliation, compromise, goodwill, and a wish for a more meaningful Union and a healthier brand of democracy, will have to also come from both sides.

Still, after all these caveats, the most pressing question in 2024 is why so many of us are swayed by Trump’s demagoguery. Without question, many people are feeling, and rightly so, that the US system has left them out, economically or culturally. That feeling of alienation fuels anger and resentment. "Yes, Trump's character is awful, but I like his determination to shake things up" is an often-used explanation. But a demagogue does not care about people, he only cares about riding the populist appeal of easy answers (like shaking things up) to power.

"Lenin is an artist, who has worked in men as others have worked in marble or metal" is a remarkable observation. Do you know who made that observation? ... Benito Mussolini. Autocrats learn from each other. For them it's not about policies, be it leftist or rightist policies. It's not even about good or bad policies, it's about that art of carving into our very souls. And such carving only leads to suffering, as Europeans know too well.

So, are we in a fight with Trump for democratic principles? Of course, in a technical sense we are, but not in the most profoundly American sense.

Let's not forget that America has not been born out of democratic ideals, but out of a desire for wealth, both material and spiritual, most elitist and undemocratic. And Trump somehow managed to make us believe that despite the US system leaving hard-working people out, he single-handedly mastered the American art of wealth building, when in fact numbers and history do not support that make-believe. This combination of idolatry towards him (and his braggadocio) and anger and resentment towards the system he is promising to shake up make for a powerful chisel in his art of carving men.

I look at this 2024 challenge by Trump’s candidacy as the ultimate test of the fears the Founding Fathers had about someone like him rising to the Presidency. Sooner or later that test was bound to occur. This threat by demagoguery (i.e. the exploitation of the human desire for easy answers by a populist leader seeking election) was foreseen and feared not just by the US Founding Fathers, it goes back as far as Socrates, in the figure of Alcibiades.

And so, one of the main axioms of our formal system for democratic governance is the existence of a personal AI assistant that would lead to a better-educated citizenry, less reliance on divine intervention, more reliance on personal responsibility, and therefore less fragility to demagoguery. AI systems through their data collection and learning can also gauge the otherwise natural progression from democracy to tyranny (as Plato concluded) and propose ways to stop that progression.

There is frustration with the delays that all court cases against Trump have been facing, and the question of whether money can buy justice in the US, which appeared in full force at the OJ Simpson trial, is gripping many of us again. It could also be the case that the courts (including the Supreme Court) are looking past the actions of Donald Trump, and trying to mindfully make decisions that would not cripple the future of the office of the Presidency while ruling on matters related to the limits of this office in this one particular case. But it’s only one possible explanation, among many other more negative ones, at this uniquely awkward time in American history.

Now, if I were to bet between a successful dismantling of our democratic institutions and their resilience, I would prefer to retain my optimism and bet on their resilience. Even more, if Trump gets elected and if we pass the four-year test, our democracy may emerge stronger. And then constitutional amendments would have to be passed, making more precise the limits of the executive, and addressing the exposed vulnerability to demagoguery that we saw in 2024.

There is no better tool for addressing that vulnerability than educational reform. But educational reform does not mean telling people, using the same old American emphasis on individual initiative, that it is up to them to lift themselves out of educational poverty. The situation is “deplorable”, not the people. A democracy like ours must find ways to ensure access to better education for all citizens, including more respect and better pay for our public school teachers. That is why John Dewey’s work on “Democracy and Education” is essential to our publication (we include a video of his work in the appendix List of Resources).

Human Morality Can also be Seen as Mathematical

Kant’s attempt at a precise mathematical theory of morality jives also with our axiom on the existence of free will (part of the formal system shown at the bottom of each essay). So, following Kant, we split the world into the physical (causality, determinism, laws of motion, etc.) and the metaphysical. Kant places morality within the metaphysical world and there he attempts to treat it rigorously just like physics treats the physical world, by establishing absolute universal principles. We’ll follow his thinking.

The clip below is a presentation of Kant’s views on morality. It is long and you may choose to stop watching at 25:58, at which point the speaker begins to elaborate on the connection between Kant’s ethical views and his political views.

Human Morality (Values) Has Priority over Democratic Principles

There will have to be undemocratic features in a functioning democracy; pure democracy is not a well-functioning democracy. And again we’ll follow Kant’s ideas in his Critique of Pure Reason by prioritizing human values over democratic principles when conflict arises. And conflict does arise, the classical example being the conflict between the democratic principle of majority rule and the human value of minority rights.

The Top and the Bottom of Each and Every Essay

Every essay shows the same diagram at the top:

and the same ending:

( Just like all posts have the same diagram at the top, they also have the same set of axioms at the bottom. The diagram at the top is about where we are now, this set of axioms is about the future.

Proposing a formal theory of democratic governance may look dystopian and infringe on a citizen’s freedom of choice. But it is trying to do exactly the opposite, enhancing citizen's independence and avoiding the anarchy that AI intrusion on governance will bring if formal rules for its behavior are not established.

One cannot worry about an existential threat to humanity and not think of developing AI with formal specifications and proving formally (=mathematically) that AI systems do indeed satisfy their specifications.

These formal rules should uphold a subset of democratic principles of liberty, equality, and justice, and reconcile them with the subset of core human values of freedom, dignity, and respect. The existence of such a reconciled subset is postulated in Axiom 2.

Now, the caveat. We are nowhere near such a formal theory, because among other things, we do not yet have a mathematical theory explaining how neural networks learn. Without it, one cannot establish a deductive mechanism needed for proofs. So it will be a long road, but eventually we will have to travel it. )Towards a Formal Theory of Democratic Governance in the Age of AI

Axiom 1: Humans Have Free Will

Axiom 2: A consistent (=non-contradictory) set of democratic principles and human values exists

Axiom 3: Citizens are endowed with a personal AI assistant (PAIA), whose security, convenience, and privacy are under citizen’s control

Axiom 4: All PAIAs are aligned with the set described in Axiom 2

Axiom 5: A PAIA always asks for confirmation before taking ANY action

Axiom 6: Citizens may decide to let their PAIAs vote for them, after confirmation

Axiom 7: PAIAs monitor and score the match between the citizens’ political inclinations and the way their representatives in Congress vote and campaign

Axiom 8: A PAIA upholds the citizen’s decisions and political stands, and never overrides them

Axiom 9: Humans are primarily driven by a search for relevance

Axiom 10: The 3 components of relevance can be measured by the PAIA. This measurement is private

Axiom 11: Humans configure their PAIAs to advise them on ways to increase the components of their relevance in whatever ways they find desirable

Axiom 12: A PAIA should assume that citizen lives in a kind, fair, and effective democracy and propose ways to keep it such

More technical justification for the need for formal AI verification can be found on the SD-AI (Stronger Democracy through Artificial Intelligence) website:articles related to this formalism are stored in SD-AI’s library section

Hello Adrian, I have made my way through the Reader's Guide for a first reading and I will be back. I can tell how important this is to you. There is enormous depth and sophistication to the material, I do hope that you will be able to draw readers who can engage with you and one another in the discussion. It is important work, especially now in 2024. One of my sadder reactions is to acknowledge how shallow most of the political, even philosophical discourse is in our country. I also am left with a more positive feeling, that even though we are in an enormous historical spasm, change is not in itself a negative. I realize that feeling under a great deal of threat, especially as a woman, I have been resistant to remembering that change in itself is not a negative.