( The diagram above ties all the individual essays together, it's helpful to keep it in mind as you read through.

Complementing this diagram and a necessary reading before proceeding with any essay in the publication, including this one, is the Reader's Guide. It is aimed at helping readers understand some of the concepts developed throughout the entire publication and avoiding repetition between the individual essays. Please look at it now, if you haven’t already; you can also review the guide at any later time through the top menu on the publication's home page.

If the Reader's Guide functions as a Prologue, the post Personal AI Assistant (PAIA) functions as an Epilogue; in that post, we begin to construct a formal approach to democratic governance based on the PAIA. We may even go out on a limb and attempt to pair that democratic governance with a more benign form of capitalistic structure of the economy, also via the PAIA.

There are two appendices to the publication, which the reader may consult as needed: a List of Changes made to the publication, in reverse chronological order, and a List of Resources, containing links to organizations, books, articles, and especially videos relevant to this publication.

The publication is “under construction”, it will go through many revisions until it reaches its final form, if it ever does. Your comments are the most valuable measure of what needs to change. )In this essay, we analyze the Support arrow in the top diagram. The main premise of this analysis is that democracy is more than just a system of government; it is also a framework designed to uphold human values. We look at the mechanisms used by a democracy to achieve this upholding, and in line with the theme of this publication, we ask how AI can be used to strengthen those mechanisms. The dangers that AI poses to democracy have received much attention, here we focus on AI’s positive potential.

In the second half of the essay, we aim a bit wider. There are distinctions between democratic principles and human values; moreover, various world democracies reconcile these distinctions in dissimilar ways. After we look at various national approaches to this value reconciliation, we ask whether AI’s language models, given their linguistic alignment with those national approaches, can facilitate global dialogue around this value reconciliation and thus increase the appeal of democratic governance across the globe.

This essay is closest in spirit to the work the author does at SD-AI (Stronger Democracy through Artificial Intelligence).

Part One: AI in the Case of a Single Democracy

Democratic Principles versus Human Values

The distinction between democratic principles and human values is a nuanced area of philosophical and political debate. Democratic principles specifically relate to rules that underpin the functioning mechanisms of a democracy, such as political participation, equality before the law, freedom of speech, and the right to vote. These principles are instrumental in maintaining a system of governance where power is vested in the people, either directly or through elected representatives.

Human values, on the other hand, are broader and more universal. They encompass moral and ethical standards that guide human behavior and societal interactions, such as respect, empathy, fairness, and responsibility. These values are not confined to any specific political system and can vary significantly across different cultures and societies.

To make it easier for the rest of the essay when we bring in AI, we will distill the interplay between democratic principles and human values and carry it into one sentence. Democracy is a system where individual rights (a key aspect of human values) are protected and where citizens have the power to influence governmental decisions (a core democratic principle).

Some Principles of Democracy Correspond One-to-One to Human Values

The three fundamental principles of democracy – liberty, equality, and justice – are intertwined with, and supportive of, the three core human values – freedom, dignity, and respect. Here is the one-to-one correspondence:

Liberty and Freedom: Liberty, a cornerstone of democratic ideology, advocates for the freedom of individuals to pursue their life paths, express their opinions, and engage in activities of their choosing, provided they do not infringe upon the rights of others. This principle aligns closely with the human value of freedom, emphasizing the importance of individual autonomy and the right to self-determination. Liberty in a democracy ensures that individuals are not unjustly constrained or censored, allowing them to develop and express their personal and cultural identities freely. (We also touch on Liberty vs Freedom in the section Free Will, Freedom, and Liberty found in the Free Will and Democracy post.)

Equality and Dignity: The democratic principle of equality holds that all individuals are entitled to equal treatment under the law, regardless of their race, gender, religion, or socio-economic status. This principle supports the human value of dignity, as it recognizes and upholds the inherent worth and value of every individual. By advocating for equal rights and opportunities, democracy reinforces the idea that each person deserves recognition as a valued member of society.

Perhaps we should divert a bit from our main futuristic and more theoretical viewpoint and mention the current reality, namely that inequality not equality is what American democracy is grappling with at this moment in time. Secondly, before we return to our main viewpoint, we should also mention that most people think that AI will increase, not decrease inequality. Following is a dialogue between Michael Sandel and David Brooks on the topic of current inequality.Justice and Respect: Justice in a democratic context is not only about legal fairness but also about creating a societal framework where individuals' rights and contributions are acknowledged and valued. This pursuit of justice reflects the human value of respect, acknowledging each person’s rights and ensuring fair treatment. Democratic justice involves both procedural fairness (fair and impartial legal processes) and distributive justice (fair distribution of resources and opportunities), contributing to a society where individuals feel respected.

However, conflicts can arise between some other democratic principles and human values

For instance, the democratic principle of majority rule may at times conflict with the protection of minority rights, a key human value. Similarly, the democratic principle of free speech can clash with the human value of respect, especially in instances of hate speech or misinformation.

Understanding and reconciling these conflicts is crucial for the healthy functioning of a democracy. The reconciliation is not easy, it often requires legal and ethical compromises to ensure both sets of principles and values are adequately represented.

For us here in this “AI, Democracy, And Human Values” publication we must make clear that when we talk about AI being aligned with human values, by human values we mean a set of reconciled democratic principles and human values. There cannot be any conflicts between the two sets, because as we clarify in the Democratic Regulations of AI article, conflicts will lead to unsound AI specifications. When we need to be precise we will use the term reconciled values instead of human values.

Because any discourse on the subject of this reconciliation is bound to be long and difficult, it would be advisable to establish some rules of communication. Such rules will acquire even more weight for us when we bring in the role of artificial intelligence (especially the language models) for this reconciliation. To help us with those rules of communication, at the above-mentioned SD-AI, we began referring to Jürgen Habermas's work on discourse ethics.

We have more than one reason to do so. His mathematically-sounding Micro-Theory of Rationality meshes well with our wish to specify AI regulations formally, and verify, also formally, that AI systems satisfy those specifications. With that wish in mind, every essay in the publication has the same section titled “Towards a Formal Theory of Democratic Governance in the Age of AI” at the bottom.

The main ideas in Habermas’ Micro-Theory of Rationality are presented in the following clip:

How Can AI Help Strengthening Democracy

The word democracy started to be overused and worn-out, at a wrong time in the relatively short history of the system it denotes, when AI is poised to rattle the foundations of that system. Democracy is the most resource-demanding of all systems of government, and the most difficult to maintain. Absorbing AI into it and making it work towards a better society will be difficult. Very difficult.

Part of that difficulty is the fact that democracy is where the relationship between man and the technology he invents has the sharpest edges. It is in a democracy where the primacy of man over technology will be the most difficult to accomplish. Aldous Huxley, whose book Brave New World was published in 1932 amid a shift towards totalitarianism in continental Europe, points out that totalitarian regimes have a much higher acceptance of technology as having the potential to drive human affairs, rather than be subordinated to them.

And Huxley did not have at his disposal the one technology that embodied his concerns most clearly. In the video clip below, at 04:34, when he says “What I may call the message of A Brave New World that it is possible to make people content with their servitude I think this can be done, I think it has been done in the past but then I think it could be done even more effectively now because you can provide them with bread and circuses and you can provide them with endless amounts of distractions and propaganda”, he did not know how pre-scient he was.

Combining AI with Mathematical Logic to Detect Disinformation

One of the strongest points we make in this publication (introduced in this section of the Reader’s Guide) is that progress in democratic governance will be achieved by combining deductive (mathematical logic) systems with AI’s statistical learning systems. Because democracy is crucially dependent on an informed citizenry, curating information is essential for effective governance.

AI can build knowledge graphs representing the relationships between entities and concepts. Mathematical logic can provide a framework for representing natural language claims and unambiguously reasoning over such knowledge graphs. This allows for the identification of logical fallacies and inconsistencies in a claim, which is common in disinformation campaigns. ML algorithms trained on large datasets of labeled examples (true and false information) can further evaluate the claim for potential disinformation.

AI can analyze a claim and identify patterns known to be associated with disinformation, such as emotionally charged text and specific keywords commonly used in misleading claims. When analyzing the claim, AI can help us understand the impact of that claim and predict potential public reactions. AI can also quickly search and build a context of information related to that claim from reliable sources.

Automated reasoning systems based on mathematical logic can then be used to determine the validity of the claim within that enriched context. In such reasoning systems, proofs are often built as explanations. As such, the proofs are not far from how humans would present their rationales for supporting or rejecting a claim, therefore helping humans predict model decisions correctly more often. Perhaps the best known example is ProoFVer: Natural Logic Theorem Proving for Fact Verification.

AI Can Help Voter Education and Representation

AI can analyze voter data and preferences to deliver customized information about candidates, ballot measures, and voting procedures. Chatbots powered by AI could answer voter questions in real time. AI can facilitate the creation of engaging educational tools, such as simulations of voting processes, interactive quizzes on political issues, and personalized voter guides.

AI-powered tools can help elected officials analyze and understand constituent sentiment, concerns, and priorities. This allows them to be more responsive and representative of the needs of their constituents. Chatbots can facilitate communication between elected officials and their constituents, providing a more accessible way for individuals to voice their opinions and concerns.

AI can analyze large datasets of constituent feedback and public opinion to help inform policy decisions, ensuring they are aligned with the needs and desires of the population. AI can also be used to model the potential impact of different policies, allowing for more informed and data-driven decision-making.

AI can analyze demographic data and voting patterns to identify communities that may be underrepresented or disenfranchised. This information can be used to develop targeted outreach and engagement strategies, ensuring that more voices are heard.

Part Two: AI and Multiple Democracies

National Approaches to Reconciliation of Values

The examples below show that the reconciliation between democratic principles and human values can vary significantly between various world democracies, based on cultural, historical, and social contexts.

United States: In the United States, the emphasis on individual freedoms is enshrined in the Constitution and the Bill of Rights. Fundamental human values such as freedom of speech, religion, and the press are rigorously protected, even when they conflict with the majority opinion. For instance, the First Amendment guarantees freedom of speech, ensuring individuals can express themselves, a core human value, regardless of the popularity of their views.

Canada: Canada's approach to multiculturalism is a unique way it reconciles democratic principles with human values. The Canadian Multiculturalism Act promotes the understanding and acceptance of diverse cultures. This policy respects individual freedoms and cultural expression, aligning with democratic principles by allowing various groups to maintain their identities within a democratic framework.

India: As the world's largest democracy, India faces the challenge of reconciling its democratic principles with immense cultural, linguistic, and religious diversity. The Indian Constitution enshrines secularism and equality before the law, regardless of religion, caste, or gender. This commitment is reflected in various laws and policies aimed at protecting minorities and promoting social justice, albeit with ongoing challenges in implementation.

Japan: In Japan, democratic principles are often harmonized with human values through consensus-building and social harmony. Japanese democracy often emphasizes collective well-being and social stability, balancing these with individual rights. The government's approach to policy-making often involves extensive consultation and efforts to achieve broad agreement, reflecting a value system that prioritizes harmony and group cohesion.

United Kingdom (UK): The UK has a long history of parliamentary democracy and is known for its unwritten constitution, which evolves through laws, judicial decisions, and conventions. A key aspect of reconciling democratic principles with human values in the UK is the protection of rights through mechanisms like the Human Rights Act 1998, which incorporates the European Convention on Human Rights into British law. This Act ensures that individuals have fundamental rights and freedoms, and that these are protected by the courts. The UK's tradition of a free press and the rule of law are also central to its democratic values.

Germany: Post-World War II, Germany's democratic system was restructured to prevent the rise of totalitarianism, with a strong focus on human dignity. The German Basic Law (Grundgesetz) places a high emphasis on human rights and aims to ensure that government authority protects these rights. For example, Germany has strict laws against hate speech and Holocaust denial, balancing the right to free speech with the need to protect human dignity and historical truth.

France: France is a republic with a strong emphasis on secularism (laïcité), a principle that underlines the separation of church and state and is seen as a way to uphold equality and unity among its citizens. This principle is deeply embedded in the French approach to democracy and is reflected in laws such as the ban on wearing conspicuous religious symbols in public schools. France's approach to human values in democracy also emphasizes individual liberty and equal rights, as outlined in its Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, a foundational document of the French Revolution.

Italy: Italian democracy emphasizes social welfare and regional autonomy. Italy's constitution, written in the wake of World War II, includes provisions to protect labor, health, and education as fundamental rights. The Italian approach often involves balancing these social rights with other democratic principles such as the rule of law and freedom of expression. Additionally, Italy's regional governments have significant autonomy, which allows for a form of democracy that respects the diverse cultural and social identities within the country.

Sweden: Known for its strong welfare state, Sweden reconciles democracy with human values by prioritizing social equality and the well-being of all citizens. Policies providing extensive social services, including healthcare, education, and social security, reflect the democratic principle of equality by ensuring a high standard of living for all, particularly the most vulnerable..

How are Those Different Approaches Reflected by AI?

We will use again the Large Language Models (LLMs) as the main example of AI systems. These LLMs are the subject of the article AI Language Models as Golems, which the reader should consult before reading this section. The Reinforcement Learning with Human Feedback (RLHF) technique described in that article is exactly the way LLMs are aligned with human values, and therefore RLHF is the central technique for us here and in all subsequent articles.

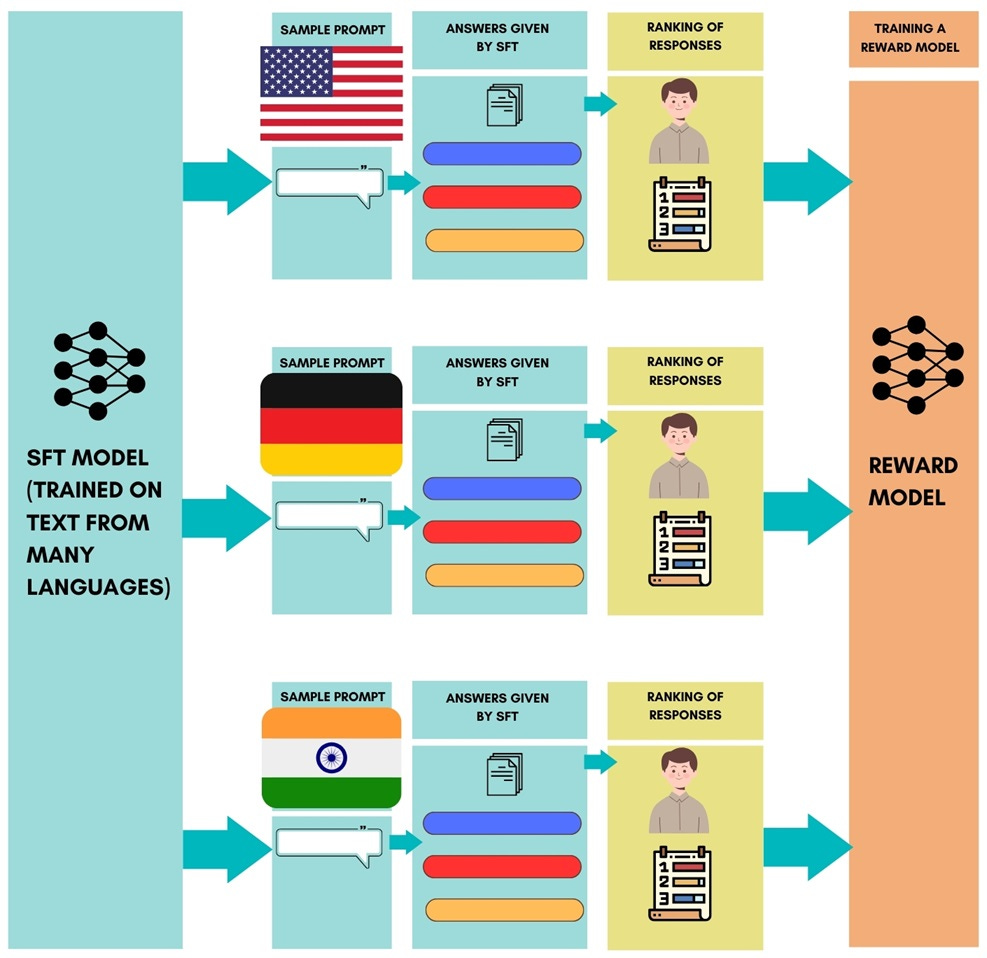

To answer the question in the title of this section, it is important to understand that these LLMs are not trained on just English text, but text from many other languages. Practically all the text available on the Internet in all languages. Moreover, they are aligned with human values (through RLHF) not only by prompts in English but by prompts in many other languages. So let’s refine step 5 (in the How LLMs are Built section of the article AI Language Models as Golems) to account for this multitude of languages. Recall that in step 5, a Reward model is built and the RLHF uses that Reward model. In the picture below, we used English, German, and Hindi as representatives of the family of languages used to build the LLM. We should represent this building of the Reward model more faithfully as follows:

It is essential for the readers of this publication to understand that the LLMs do not present an objective reality but rather a reality filtered through their training sets and further filtered by the human values of their builders through the RLHF technique.

We have seen above that each democracy is characterized by its unique set of values and perceptions of reality and that these differences are shaped by historical, cultural, social, and political factors. So there is no surprise that LLMs will reflect these diverse values.

The risk of perpetuating biases and misrepresentations from the large training datasets is significant, especially if the models are not trained on sufficiently diverse and balanced datasets. Moreover, the interpretation of AI-generated content can vary based on cultural and individual perspectives, leading to varied reactions and understandings.

While we acknowledge these challenges, the LLMs also offer unique opportunities to enhance global dialogue and understanding. They can be used to translate and interpret content across languages and cultures, making information more accessible and cultivating cross-cultural understanding.

Additionally, by presenting multiple perspectives on a given issue, they can encourage critical thinking and a more nuanced understanding of global issues. And with more critical thinking and more understanding, AI (and the LLMs in particular) can increase the value of democratic governance across the globe.

( Just like all posts have the same diagram at the top, they also have the same set of axioms at the bottom. The diagram at the top is about where we are now, this set of axioms is about the future.

Proposing a formal theory of democratic governance may look dystopian and infringe on a citizen’s freedom of choice. But it is trying to do exactly the opposite, enhancing citizen's independence and avoiding the anarchy that AI intrusion on governance will bring if formal rules for its behavior are not established.

One cannot worry about an existential threat to humanity and not think of developing AI with formal specifications and proving formally (=mathematically) that AI systems do indeed satisfy their specifications.

These formal rules should uphold a subset of democratic principles of liberty, equality, and justice, and reconcile them with the subset of core human values of freedom, dignity, and respect. The existence of such a reconciled subset is postulated in Axiom 2.

Now, the caveat. We are nowhere near such a formal theory, because among other things, we do not yet have a mathematical theory explaining how neural networks learn. Without it, one cannot establish a deductive mechanism needed for proofs. So it will be a long road, but eventually we will have to travel it. )Towards a Formal Theory of Democratic Governance in the Age of AI

Axiom 1: Humans Have Free Will

Axiom 2: A consistent (=non-contradictory) set of democratic principles and human values exists

Axiom 3: Citizens are endowed with a personal AI assistant (PAIA), whose security, convenience, and privacy are under citizen’s control

Axiom 4: All PAIAs are aligned with the set described in Axiom 2

Axiom 5: A PAIA always asks for confirmation before taking ANY action

Axiom 6: Citizens may decide to let their PAIAs vote for them, after confirmation

Axiom 7: PAIAs monitor and score the match between the citizens’ political inclinations and the way their representatives in Congress vote and campaign

Axiom 8: A PAIA upholds the citizen’s decisions and political stands, and never overrides them

Axiom 9: Humans are primarily driven by a search for relevance

Axiom 10: The 3 components of relevance can be measured by the PAIA. This measurement is private

Axiom 11: Humans configure their PAIAs to advise them on ways to increase the components of their relevance in whatever ways they find desirable

Axiom 12: A PAIA should assume that citizen lives in a kind, fair, and effective democracy and propose ways to keep it as such

More technical justification for the need for formal AI verification can be found on the SD-AI (Stronger Democracy through Artificial Intelligence) website:articles related to this formalism are stored in SD-AI’s library section