( The diagram above ties all the individual essays together, it's helpful to keep it in mind as you read through.

Complementing this diagram and a necessary reading before proceeding with any essay in the publication, including this one, is the Reader's Guide. It is aimed at helping readers understand some of the concepts developed throughout the entire publication and avoiding repetition between the individual essays. Please look at it now, if you haven’t already; you can also review the guide at any later time through the top menu on the publication's home page.

If the Reader's Guide functions as a Prologue, the post Personal AI Assistant (PAIA) functions as an Epilogue; in that post, we begin to construct a formal approach to democratic governance based on the PAIA. We may even go out on a limb and attempt to pair that democratic governance with a more benign form of capitalistic structure of the economy, also via the PAIA.

There are two appendices to the publication, which the reader may consult as needed: a List of Changes made to the publication, in reverse chronological order, and a List of Resources, containing links to organizations, books, articles, and especially videos relevant to this publication.

The publication is “under construction”, it will go through many revisions until it reaches its final form, if it ever does. Your comments are the most valuable measure of what needs to change. )Democracy has long been regarded as one of the most cherished and effective forms of governance, allowing citizens to participate in decision-making processes and shaping the course of their society.

A fundamental question is this: can democracy truly flourish without citizens possessing and exercising their free will? In this article, we will look at the relationship between free will and democracy, trying to answer that question in the negative.

There is widespread belief among AI technologists that a new kind of citizen will emerge in the near future, a citizen endowed with a personal AI assistant running on personal devices, or in cyberspace, or more probably in both. The functionality of such an assistant is a big subject, deserving of a full article on its own. In this essay, we take the existence of such a personal assistant as an axiom.

And therefore, a second question accompanies the fundamental one we asked above. Namely, what are the ways this personal AI assistant will affect the exercise of free will in general, and in particular for what democracy needs from its citizens, like independent thinking, being informed, and participation in decision-making?

The Debate on Free Will

Free will is the concept that we humans have the power to make choices and decisions that are not determined by forces that are external to us. It is an embodiment of the belief that we as individuals possess the autonomy to act according to our own desires, values, and beliefs. However, the apparently simple proposition that humans possess free will is much-debated in philosophy and psychology.

Philosophers have pondered the nature of free will for centuries, with some arguing that free will is just an illusion. They say that if determinism is true, i.e. every physical event is completely determined by prior events through the laws of nature, then free will cannot exist. And therefore, the classical argument against free will assumes that determinism is indeed true.

But this is just an assumption, an assumption that has been challenged by quantum mechanics. The laws of quantum mechanics are probabilistic, not deterministic. Many possible events could follow a given event, each with its own probability. Now, one should also add that the debate of whether there may be another deterministic layer of reality underneath the probabilistic layer of quantum mechanics, as Einstein believed and as unlikely as that may be, has never been settled.

We simply do not know whether determinism is true or indeterminism is true. Regardless, this "don't know" conclusion invalidates the classical argument against free will because that argument assumes that determinism is true.

Modern psychologists have tried to save the classical argument. Even though they concede that determinism may be false in physics, they argue based on studies they've done that a human's actions are still determined by prior events in that human's life and socio-economic conditioning.

Modern philosophers have also tried to save the argument by saying that indeterminism is also incompatible with free will. They say that if human decisions are not caused by anything, then they are random, and if they just pop up randomly, then they cannot arise from free will either.

These arguments have yet to be settled. And while I am acknowledging the arguments here, I have to say that they nevertheless sound forced to me. I think, as most of us do, that I have free will, and I don’t lose any sleep over the fact that what I do tomorrow may have been pre-determined at Big Bang time.

More to the point, while the debate continues, it is crucial to acknowledge that free will, whether philosophical or psychological, is a cornerstone of individual agency. What is important in my view is that we believe we have free will. And therefore, in all my articles here and in my work at SD-AI we take the existence of free will as an axiom.

Democratic Process, Its Principles, and Its Essence

Democracy is a political system where power is vested in the hands of the people, who exercise it either directly or through elected representatives.

To make that exercise of power possible, the democratic process relies on citizens' ability to make free choices that reflect their interests. The exercise of power can be done through elections, referendums, and public discourse.

The fundamental principles of democracy include political equality, individual freedoms, the rule of law, and, most importantly for our discussion, citizen participation.

So in this publication, we will treat the essence of democracy as empowering citizens to exercise their free will (whose existence we take as an axiom) within the framework of the law.

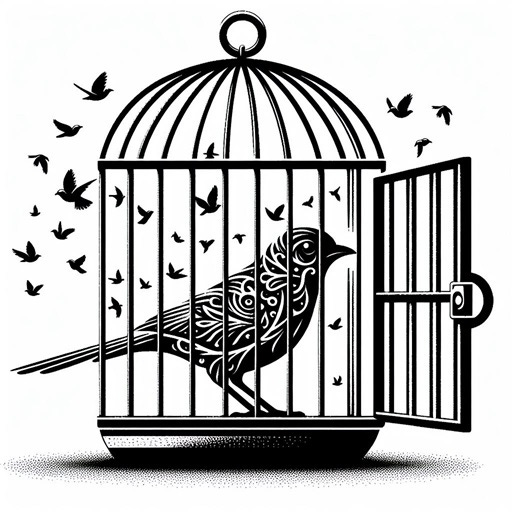

Free Will, Freedom, and Liberty

Because this article is foundational to the entire publication we need to be careful with these three terms. While they are often used interchangeably, there are subtle but important distinctions between them.

As we saw above, free will refers to the ability to make choices freely and independently. It is a philosophical concept that deals with the question of whether humans have genuine agency and control over their actions, or whether their choices are predetermined. It focuses on the internal capacity for choice. It asks whether we could have chosen differently, even if all other factors remained the same.

Freedom is a human value and it refers to the absence of external constraints or restrictions. It is a broader concept that encompasses various aspects of life, including political, social, and economic freedom. It focuses on the external environment and the opportunities available to individuals. It asks whether there are external factors preventing someone from acting on their choices.

Liberty is a democratic principle often used synonymously with freedom, but can also carry a stronger connotation of individual autonomy and self-determination. It emphasizes the right to live one's life as one chooses, free from undue interference by others. It focuses on the individual's ability to act on their own will and pursue their own goals. It asks whether individuals have the power and resources to act on their choices.

We can summarize these distinctions as follows. Free will is about the internal capacity for choice, freedom is about the absence of external constraints, and liberty is about the ability to act on one's own will.

For a simple analogy, imagine a bird in a cage

If the bird has free will, it can choose whether to sing or remain silent. Internal choice:

If the cage door is open, the bird has freedom to fly away. Absence of external constraints:

However, if the bird's wings are clipped, it lacks the liberty to actually fly, even if the cage is open. Ability to act on a choice made:

Free will and democracy in philosophical discourse

As we mentioned above, the capacity to choose among alternatives and to act based on one's own decisions sits at the core of the very concept of democracy. Here we look at the diverse philosophical views on this relationship.

This diversity of thought has important implications for us in this publication, especially when we look at the main problem of AI, the alignment with human values, and also when we look at using AI for a formal theory of democratic governance (which we separate into the appendix Personal AI Assistant).

To make it easier to relate to these philosophers, I emphasize in italics for each philosopher the ideas that are most relevant to us. I link to them from many places in the other essays.

Ancient and Medieval Philosophers

Aristotle (384–322 BCE), particularly in his works “Politics” and “Nicomachean Ethics”, posits that the exercise of free will is essential for achieving eudaimonia, or human flourishing. Aristotle argues that a good life is lived according to virtue, which requires rational deliberation and the ability to make free choices. In a democratic context, this means that citizens must be capable of participating in the political process, making informed decisions, and contributing to the common good. For Aristotle, democracy provides the framework within which individuals can exercise their free will in pursuit of collective and personal virtue.

Saint Augustine (354–430) offers a theological perspective on free will and its implications for governance in his writings, such as “The City of God”. He emphasizes the importance of free will in moral responsibility, arguing that individuals must have the capacity to choose between good and evil to be accountable for their actions. In the context of democracy, Augustine's views suggest that a just society requires individuals to exercise their free will in alignment with divine justice and moral law, cultivating a community grounded in ethical principles and mutual respect.

Enlightenment Thinkers

The contributions of John Locke (1632–1704) to the philosophy of free will and democracy are foundational to modern liberal thought. In his “Second Treatise of Government”, Locke argues that individuals possess natural rights to life, liberty, and property, which they exercise through their free will. He contends that the legitimacy of government derives from the consent of the governed, who exercise their free will in choosing their representatives and shaping laws. This social contract ensures that the government respects and protects individual freedoms, creating a democratic society where free will is both a right and a responsibility.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778), in his seminal work “The Social Contract”, explores the tension between individual free will and the collective will of the community. Rousseau introduces the concept of the "general will", which represents the collective interest of the people. He argues that true freedom is found in obedience to the general will, as it reflects the common good. For Rousseau, democracy involves a harmonization of individual free will with the collective decision-making process, ensuring that personal liberty contributes to the welfare of the entire community.

Modern Philosophers

Immanuel Kant (1724–1804). Kant’s moral and political philosophy, particularly in works like “Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals” and “The Critique of Practical Reason”, emphasizes the role of autonomy and free will in ethical behavior and governance. Kant argues that true freedom is the ability to act according to rational moral laws that one gives oneself, independent of external coercion. In a democratic society, this means that citizens must have the autonomy to participate in the legislative process and to abide by laws they have rationally endorsed. Democracy, for Kant, is the political expression of moral autonomy, where free will is exercised in the pursuit of universal principles of justice.

John Stuart Mill (1806–1873), in his influential work “On Liberty”, argues that the freedom to express one's opinions, pursue one's interests, and engage in public discourse is fundamental to personal and societal development. He asserts that free will must be safeguarded from both governmental and societal encroachments, as it is the foundation of personal autonomy and democratic participation. Mill's utilitarian framework links free will to the maximization of overall happiness, suggesting that a society that respects and promotes individual liberty will ultimately be more just and prosperous.

Twentieth-Century Perspectives

Hannah Arendt (1906–1975), in her works such as “The Human Condition and “On Revolution”, looks at the role of free will in political action and public life. Arendt distinguishes between the private realm of necessity and the public realm of freedom, where individuals engage in collective deliberation and decision-making. She argues that true political freedom involves the capacity to initiate new actions and to participate in the creation of a common world. (This capacity to initiate new actions is also argued eloquently by Noam Chomsky in the video clip we listed in List of Resources). For Arendt, democracy is the political arena where free will is exercised through public discourse and collective action, enabling individuals to shape their shared reality.

John Rawls (1921–2002), in his seminal work “A Theory of Justice”, presents a vision of democracy grounded in the principles of justice and fairness. Rawls argues that a just society is one in which individuals exercise their free will within a framework of fair institutions that protect basic liberties and ensure equal opportunities. His concepts of the "original position" and the "veil of ignorance" highlight the importance of impartial decision-making in creating a democratic society that respects and enhances individual autonomy. For Rawls, democracy is the institutionalization of principles that allow free will to flourish in a context of fairness and mutual respect.

The individual versus the collective

Nations around the world view the three terms (free will, freedom, liberty) with some notable differences. Many such differences can be explained by their respective views on the relationship between the individual versus the collective.

The US has a strong tradition of individualism and personal liberty. This is reflected in the emphasis on individual rights and freedoms in the US Constitution. Americans tend to see free will as more central to a functioning democracy, as it allows citizens to make informed choices and hold their government accountable.

The US is unique (do not read unique as being superior!) among democracies with this primacy of the individual versus the collective. Other democracies view a larger role for the collective, especially with respect to social welfare and the guidance of the economy.

For example, although the UK also values individual liberty and sees free will as a cornerstone of democracy, the UK has a more collectivist political culture than the US, with a stronger emphasis on social welfare and government intervention in the economy. Australia too shares many similarities with the UK and the US in terms of its political system and values but Australia also has a unique and strong emphasis on egalitarianism and a "fair go" for all.

The traditions of India, as the world's largest democracy, value the interconnectedness of all things and the influence of karma, leading to different understandings of free will compared to Western individualistic perspectives. Japan emphasizes social harmony and group consensus. There is less emphasis on individual free will as a driving force in the democratic process compared to Western democracies.

France's tradition of republicanism emphasizes civic virtue and the role of the state in promoting the common good. This leads to a greater emphasis on government responsibility in shaping society and ensuring equality, balancing individual freedoms with collective welfare.

Germany's commitment to democratic values and individual freedom is heavily influenced by its historical experiences with authoritarianism. Its political culture emphasizes consensus-building and social responsibility, ensuring that individual rights are protected within a framework that prioritizes collective well-being and historical accountability.

Free Will and Citizen Participation

In a democracy, regardless of the differences outlined above, the ability of its citizens to make choices freely is needed for it to function effectively. Without free will, citizens would be reduced to passive observers rather than active participants.

Here are some ways in which free will is essential for citizens participation:

Voting: Voting is the foundation of democracy; it allows citizens to express their preferences and select their leaders. Without free will, voters would be unable to make informed decisions based on their beliefs and values, thus undermining the legitimacy of the electoral process.

Political Activism: Free will empowers individuals to engage in political activism, such as participating in protests, joining advocacy groups, and exercising their right to free speech. These actions are vital for holding leaders accountable and advocating for change.

Informed Decision-Making: In a democracy, citizens are expected to assess information, analyze policy proposals, and make informed decisions. Free will enables citizens to evaluate competing ideas and choose the course of action they believe is best for their community or nation.

Public Engagement: Free will encourages citizens to engage in public debates and to listen to diverse perspectives. Without the freedom to express their opinions, public discourse would become stagnant, hindering the growth and development of society.

Checks and Balances: The democratic system relies on checks and balances to prevent the concentration of power in the hands of a few. Free will empowers citizens to scrutinize and challenge the actions of their government, ensuring that it remains accountable and responsive to the people's will.

Challenges to Free Will in a Democracy

While free will is indispensable for democracy, some challenges can hinder its full realization within the democratic process. These challenges include:

Socioeconomic Factors: Socioeconomic disparities can limit the ability of some individuals to exercise their free will effectively. Economic hardship, lack of access to education, or discrimination can hinder their participation in the democratic process.

Manipulation: Citizens may be subjected to various forms of manipulation, such as misinformation, propaganda, or emotional appeals, which can influence their decisions and compromise their free will.

Polarization: Political polarization can lead to an environment where individuals are pressured to conform to extreme ideologies, potentially limiting their ability to make independent choices.

External Influences: International actors, interest groups, and foreign governments may attempt to interfere in a nation's democratic processes, manipulating public opinion and undermining free will.

Voter Suppression: Measures aimed at suppressing voter turnout, such as restrictive voting laws or gerrymandering, can undermine citizens' ability to exercise their free will through the electoral process.

AI’s Impact on Free Will in a Democracy

Let’s bring in AI since the theme of our publication is the interaction between AI and democracy. It is almost certain that a new type of citizen will emerge soon, a citizen endowed with a personal AI assistant (PAIA), i.e. software running on personal devices and/or in cyberspace. A PAIA with a physical presence is already being experimented with, especially for elderly and people with special mobility disabilities.

How will this PAIA impact free will with respect to the democratic process? Below are some potential benefits and drawbacks.

Potential benefits

Enhanced decision-making: AI assistants can provide access to vast amounts of information and analyze complex data, helping individuals make more informed and more rational decisions.

Reduced cognitive biases: AI assistants can be trained to identify and mitigate cognitive biases that can cloud human judgment.

Increased efficiency and productivity: AI assistants can automate tasks and manage schedules, freeing up time and mental energy for individuals to focus on more meaningful pursuits.

Personalized experiences: AI assistants can learn individual preferences and tailor recommendations and assistance accordingly, potentially leading to a more fulfilling and self-directed life.

Potential drawbacks:

Overreliance and dependence: Excessive reliance on AI assistants for decision-making could weaken individual autonomy and critical thinking skills.

Manipulation and control: AI assistants could be used to manipulate individuals by subtly influencing their choices or restricting their access to information.

Erosion of privacy: AI assistants collect vast amounts of personal data, raising concerns about privacy violations and potential misuse of this information.

Algorithmic bias: AI algorithms can reflect and amplify existing biases in society, potentially leading to discriminatory outcomes and limiting individual choices.

In conclusion, democracy needs the premise that citizens possess free will, allowing them to actively engage in the political process, make informed decisions, and shape the future of their society. Without free will, a democracy would be reduced to a mere facade, devoid of genuine citizen participation. We assume that a new type of citizen will emerge in the age of AI, a citizen endowed with a personal AI assistant. The democratic process must continually strive to protect and enhance the autonomy and agency of its citizens, and ensure through legislative regulations that their personal AI assistants enhance rather than infringe on that autonomy and agency.

( Just like all posts have the same diagram at the top, they also have the same set of axioms at the bottom. The diagram at the top is about where we are now, this set of axioms is about the future.

Proposing a formal theory of democratic governance may look dystopian and infringe on a citizen’s freedom of choice. But it is trying to do exactly the opposite, enhancing citizen's independence and avoiding the anarchy that AI intrusion on governance will bring if formal rules for its behavior are not established.

One cannot worry about an existential threat to humanity and not think of developing AI with formal specifications and proving formally (=mathematically) that AI systems do indeed satisfy their specifications.

These formal rules should uphold a subset of democratic principles of liberty, equality, and justice, and reconcile them with the subset of core human values of freedom, dignity, and respect. The existence of such a reconciled subset is postulated in Axiom 2.

Now, the caveat. We are nowhere near such a formal theory, because among other things, we do not yet have a mathematical theory explaining how neural networks learn. Without it, one cannot establish a deductive mechanism needed for proofs. So it will be a long road, but eventually we will have to travel it. )Towards a Formal Theory of Democratic Governance in the Age of AI

Axiom 1: Humans Have Free Will

Axiom 2: A consistent (=non-contradictory) set of democratic principles and human values exists

Axiom 3: Citizens are endowed with a personal AI assistant (PAIA), whose security, convenience, and privacy are under citizen’s control

Axiom 4: All PAIAs are aligned with the set described in Axiom 2

Axiom 5: A PAIA always asks for confirmation before taking ANY action

Axiom 6: Citizens may decide to let their PAIAs vote for them, after confirmation

Axiom 7: PAIAs monitor and score the match between the citizens’ political inclinations and the way their representatives in Congress vote and campaign

Axiom 8: A PAIA upholds the citizen’s decisions and political stands, and never overrides them

Axiom 9: Humans are primarily driven by a search for relevance

Axiom 10: The 3 components of relevance can be measured by the PAIA. This measurement is private

Axiom 11: Humans configure their PAIAs to advise them on ways to increase the components of their relevance in whatever ways they find desirable

Axiom 12: A PAIA should assume that citizen lives in a kind, fair, and effective democracy and propose ways to keep it as such

More technical justification for the need for formal AI verification can be found on the SD-AI (Stronger Democracy through Artificial Intelligence) website:articles related to this formalism are stored in SD-AI’s library section

Thanks for sharing this, Adrian- I've long wondered about the future of Personal AI Assistant, and now I think I have a better understanding. For one, I'd like them to be able to make my morning tea/coffee. So maybe one day. Hope you're well this week, Adrian-

Hi Adrian, thanks for touching base. I checked out your sub stack and read your article “Free Will And Democracy”. Interesting stuff. I am more of an institutionalist, meaning while I believe we have some degree of “free will,” I also believe that free will is greatly defined and, I would go so far as to say, severely constrained, by the institutions that define our society, our family, our individual lives. Within the limits of those institutions, we have a degree of free will. Beyond the institutions, a closely related factor of “culture” also greatly define, and severely constrain, our free will. In your article, of a subsection called “National Differences” – those national differences exist substantially due to the differences in institutions, as well as the differences in culture. In the two of these are generally mutually reinforcing of each other. There are loads of examples I could give which illustrate these dynamics, but I’m sure you know what I mean.

Thanks, all the best